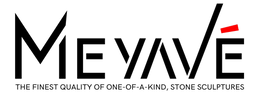

Zimbabwean sculptor Joseph Ndandarika (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Our journey through the history of Zimbabwean stone sculpture starts with a glimpse into the High Middle Ages before progressing to the pivotal influences of three 20th-century pioneers.

Great Zimbabwe: An Architectural Marvel

Stone walls of Great Zimbabwe

The roots of modern Zimbabwean stone sculpture trace back to an ancient Shona civilization. Built between the 11th and 15th centuries, Great Zimbabwe is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the southeastern hills of modern-day Zimbabwe. The ancient city, once home to over 10,000 people, is renowned for its massive stone structures. Its most monumental edifice spans an incredible 820 feet, with walls as high as 36 feet. The city’s name, “Great Zimbabwe,” translates to “Big Stone Houses” in the Shona language, aptly describing this remarkable site.

Massive stone wall at Great Zimbabwe

Amazingly, the builders constructed these colossal walls without mortar or cement. They stacked carefully selected stones so that their weight and precise placement would create a stable structure. When European explorers discovered the abandoned ruins during the 1800s, they were shocked by its advanced engineering. Unable to accept that indigenous Africans could have constructed such impressive structures, they erroneously attributed the architecture to foreign powers. The stone ruins continue to captivate historians, archaeologists, and visitors alike.

Soapstone sculptures found in the ruins of Great Zimbabwe

Within the walls of the ruins, explorers discovered soapstone sculptures about sixteen inches tall, standing on columns over a yard in height. These statues, depicting bird-like creatures with human features, likely symbolized royal authority. Scholars speculate that these birds may have even represented the ancestors of the city’s medieval rulers. While Great Zimbabwe didn’t directly influence modern stone sculpting, the city’s grandeur, cultural significance, and stunning stonework laid the foundation for the artistic traditions that would emerge in the region.

Joram Mariga, the Father of Zimbabwean Sculpture

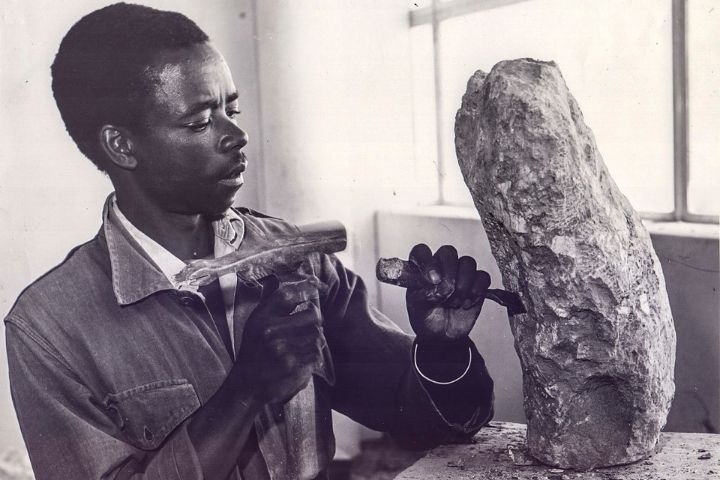

Zimbabwean sculptor Joram Mariga and one of his artworks

Stone carving as an art form didn’t become a tradition until it experienced a revival in the 1950s when its modern renaissance began. Joram Mariga was a Shona artist born into a family of woodcarvers. He started carving wood when he was around eight years old. In 1957, when he was 30, he unintentionally discovered a supply of valuable green Inyanga soapstone in what was then known as Eastern Rhodesia.

Initially unaware of its potential, Mariga began using the softer stone to create utensils and small figurines. He later transitioned from working with soapstone to experimenting with firmer materials. When the country’s tourism industry developed, Mariga and other sculptors started producing stonework realistically depicting wildlife, which they predominantly sold to tourists. Due to his influence on the sculptural movement known as “Shona sculpture,” people often referred to Joram Mariga as the father of Zimbabwean sculpture.

Frank McEwen, a Catalyst of Change

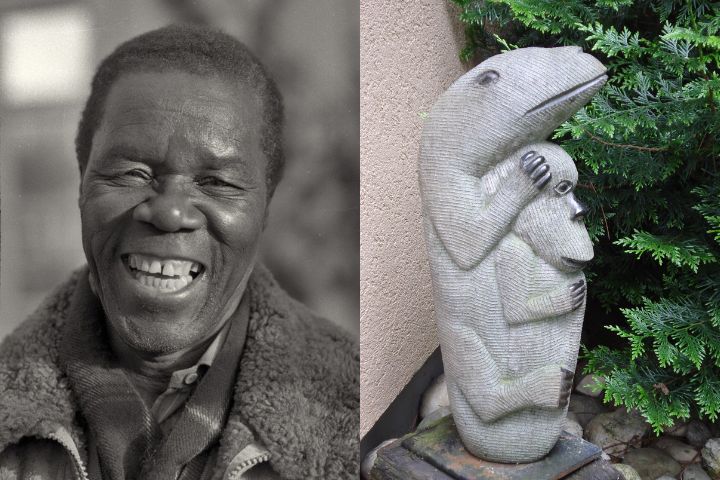

Former director of the National Gallery of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Frank McEwen

During the 1950s, the National Gallery of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) hired English artist Frank McEwen as the visionary founding director. While the board of directors was intent on stocking its halls with artwork by 15th to 18th-century European artists known as “Old Masters,” McEwen believed that the gallery’s success depended on including African art in its collection.

When McEwen met Joram Mariga in the 1950s, he recognized the untapped potential of local artists. He established an unofficial workshop school at the gallery, where he encouraged local artists to experiment with stone as a medium. Under his guidance, these artists began to explore the artistic potential of different types of rocks. McEwen supplied materials, a workspace, constructive feedback, and unwavering support to the sculptors. Initially, the workshop operated independently within the gallery. When its sculptures gained recognition in international exhibitions, the gallery’s board of directors accepted the unique African artworks as part of its collection.

Tom Blomefield and the Birth of Tengenenge

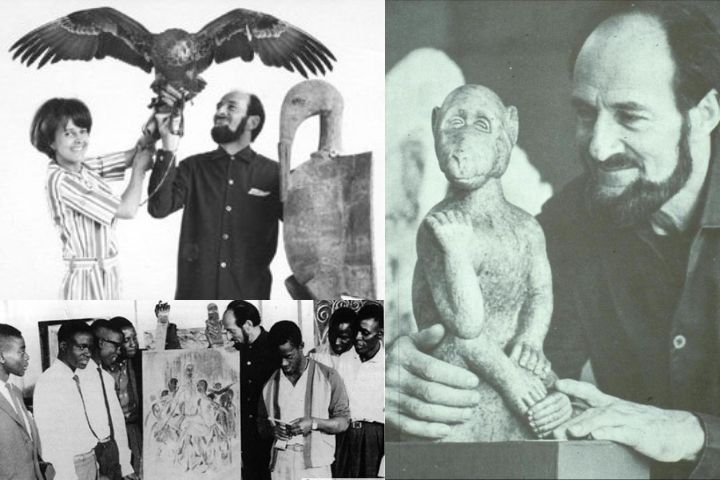

Tom Blomefield (left) and an artist from Tengenenge

Our historical journey takes us to Tengenenge, a creative haven of artists in the Guruve District of Zimbabwe. The name “Tengenenge,” translates to “The Beginning of the Beginning” in the local Korekore dialect of the Shona language. The initial generation of artists at Tengenenge produced sculptures that English gallery director Frank McEwen incorporated into the Rhodes National Gallery’s expanding collection.

Tom Blomefield, a white South African-born farmer, established the Tengenenge Sculpture Community in 1966 on what was once a tobacco farm and chromium mine. However, due to international sanctions against Rhodesia’s white government, Blomefield’s farm and mine became unviable. In search of an alternative income source for his workforce, Blomefield discovered a valuable resource on the farm—an outcrop of hard serpentine stone. He secured the right to mine this stone for sculpting purposes. Blomefield remained the director of Tengenenge until 2007, passing the torch to accomplished Zimbabwean sculptor Dominic Benhura.

Zimbabwean sculptor and director of Tengenenge, Dominic Benhura

Although both Frank McEwen and Tom Blomefield played vital roles in shaping Zimbabwe’s artistic landscape, they held differing views on the direction of the local sculpture movement. McEwen preferred to provide structured training to selected Zimbabwean artists. In contrast, Blomefield welcomed artists from various countries, including Angola, Malawi, and Mozambique, into the predominantly Shona community at Tengenenge, regardless of their training.

According to Australian-born artist and art critic Celia Winter-Irving, who had resided at Tengenenge for several months, Tom Blomefield did not approach his role with an attitude of condescending or domineering authority, nor did he try to force or enforce his Western way of living on the artists he was mentoring.

During Tengenenge’s peak, art sales supported a community of over 1,200 members. However, due to prolonged economic adversity, Zimbabwe’s tourism industry has almost collapsed, and less than 100 artists still reside at Tengenenge.

Now that we have a deeper understanding of the historical influences shaping Zimbabwean stone sculpture, our next blog post will delve into the various types of stones that breathe life into these captivating artworks. Stay tuned for more on this fascinating subject.

What aspects of Zimbabwean stone sculpture’s remarkable history intrigued you the most? I’d love to hear your thoughts and questions in the comments below.